Religious Accommodations: Unanswered Questions in Patterson v. Walgreen Co.

-

Jeremy Fricke

Jeremy Fricke

- Published on

Issues in Question:

- Do organizations need to provide a complete accommodation for a religious accommodation to be reasonable? In other words, if my religion requires no work on Saturdays, is my employer required to provide me all Saturdays off?

- What counts as a reasonable accommodation?

- At what point is an accommodation an “undue hardship” on the employer?

Darrell Patterson was deeply committed to his faith as a Seventh-day Adventist, as well as his job as a trainer for Walgreens. Seventh-day Adventism is a Protestant Christian denomination, known for a commitment to conservative values as well as an emphasis on diet and health – but what they are most known for is an insistence on recognizing the Sabbath from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday, in line with Judaism. Patterson made a deal with his manager that they would try to avoid scheduling him on Saturdays. If he had to be scheduled on Saturdays, he would be allowed to find an “equal” replacement. There were only a few times over his six years with the company where he could not be accommodated, each receiving progressive punishment, and in 2011 he was fired for missing an emergency training, where he was expected to train a large number of call-center workers for a shift in job responsibilities.

He sued in 2014, alleging that Walgreens did not reasonably accommodate him. Walgreens won at the 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals because they found it unreasonable for Patterson to expect Walgreens to guarantee that he would never work a Friday evening or Saturday. The Supreme Court did not review the case because the lower court’s decision did not seem to turn on the details of the questions, as discussed below.

On February 25th, 2020, the Supreme Court declined to review the lower court ruling in the case of Patterson v. Walgreen Co. To oversimplify, this means that the decision was returned to that lower court and that the decision is only binding to citizens under their purview, in this case, the 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals. But, the case might have answered a wide variety of questions about religion, employee rights, and employer rights in the United States.

A few terms are relevant for discussion are from Title VII, which prohibits employment discrimination “because of the individual’s religion” and is expected to provide a reasonable accommodation unless it were to cause an undue hardship on the employer. Reasonable accommodation and undue hardship have been defined differently by a variety of courts. Who gets to decide what is reasonable? At what point is the hardship “undue” or de minimis?

Is the accommodation only reasonable if it is a full accommodation? The only reasonable accommodation in Patterson’s view was to abstain from work on Saturdays, as his religion teaches that there is no room for negotiation when observing the Sabbath. Walden v. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention says that “a reasonable accommodation is one that eliminates the conflict between employment requirements and religious practices”. But, accommodation is not expected at all costs.

Undue hardship has also been defined differently in various cases. The most commonly cited case in employment religious discrimination is TWA v. Hardison (1977) which determined that undue hardship could be defined as a de minimis (minimal) cost, which has not really helped organizations figure out the correct approach. For Walgreens, it was an undue hardship to require other trainers to always cover Saturdays or to never have Patterson attend Friday night or Saturday training. But, if an undue burden is anything that can be seen as costing the company any amount of money or time, then religion would never be accommodated in the workplace. This is not a valid approach either.

The Supreme Court is hoping for a case that would identify the following questions with clarity: (1) Is the employer required to provide partial accommodation even if the full accommodation would impose undue hardship? (2) Can an employer show that an accommodation would impose an undue hardship based on speculative harm? The Supreme Court has also expressed an interest in revisiting the de minimis standard as well. These questions would resolve many of the difficulties that organizations have in determining expected accommodations, but this was not the right case for these to be resolved.

In my view, organizations have a responsibility to do what they can do to accommodate religious practices in the workplace (within reason). The burdens of time and cost on the organization are dramatically reduced if the organization is prepared, organized, strategic, and literate regarding religion in the workplace. A conversation with someone who has prepared for religious inclusion in the workplace would have likely brought out potential strategies to accommodate Patterson – for example, there seemed to be no conversation about whether Walgreens or Patterson could record training for later use.

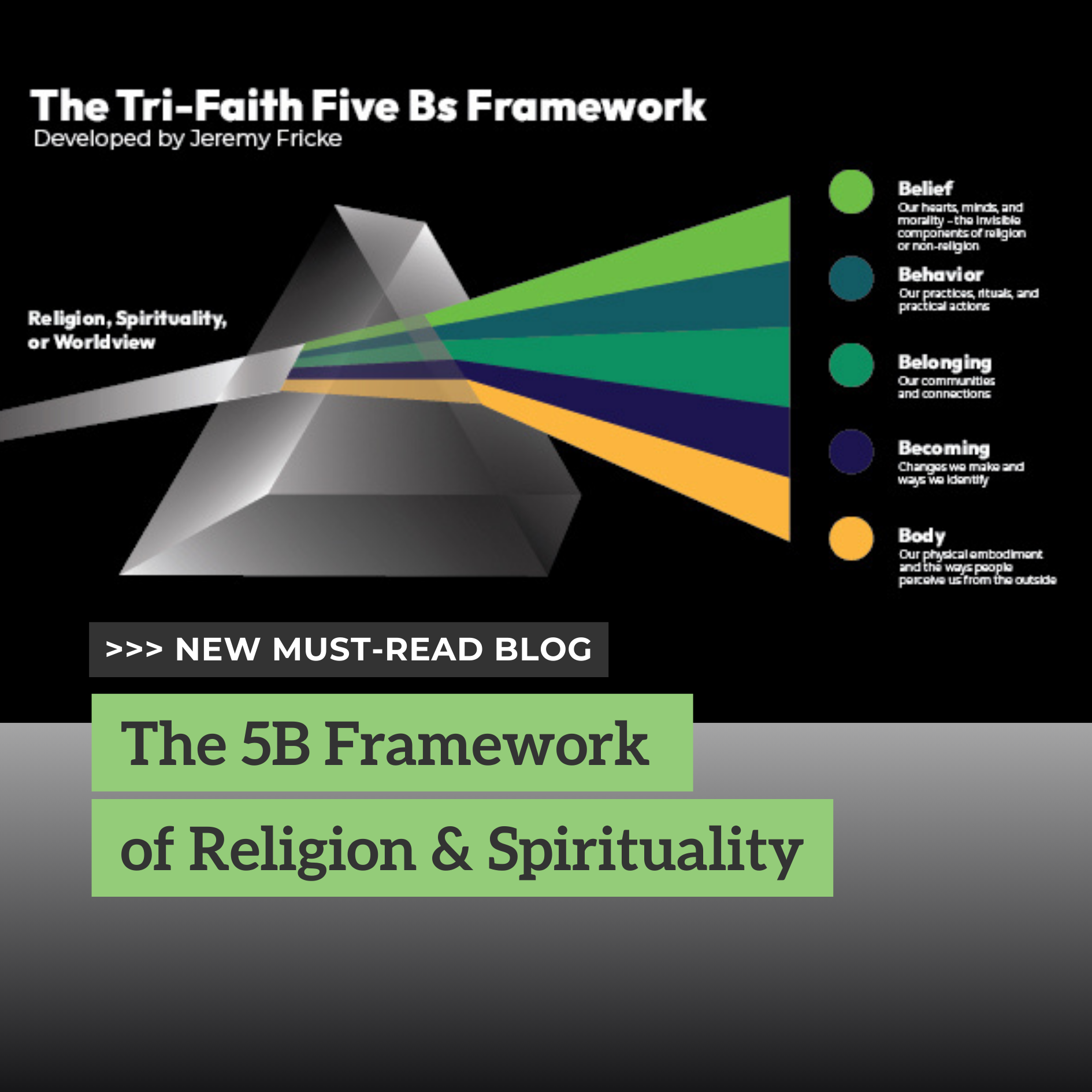

Many people are confused with the ranging definitions and legal jargon with accommodations. This is why Tri-Faith Initiative is working to provide education and support for organizations trying to navigate religious matters in the workplace, whether they are legal issues, inclusion strategy, or religious literacy for professionals.

For more reading:

Patterson v. Walgreen Co. (Case Text)

18-349 Patterson v. Walgreen Co. (Supreme Court of the United States)

U.S. Supreme Court turns away religious bias claim against Walgreens (Reuters)

Spread the Word